Cathodic Protection and Corrosion Engineering - The basics

An overview of the basic terms and terminology used in cathodic protection and corrosion engineering application.

The basic yet important concepts

The below content aims at summarizing some of the essential concepts and definitions that any cathodic protection or corrosion engineer will use during his/her career. Cathodic protection and corrosion modeling solutions rely on these concepts.

The content of this page is the result of constant ongoing review, feel free to contact us would you have any suggestions related to additional content you would like to see appear.

Oxidation & Anode

Oxidation refers to the loss of one or more electrons from an atom or molecule resulting in a positively charged ion. This phenomenon occurs any time electrons are released by an atom or molecule. As an electron is released, the atom or molecule decreases in negative charge. The location (commonly an electrode) where oxidation occurs is conventionally named an anode.

Reduction & Cathode

Reduction refers to the gain of one or more electrons from an atom or molecule resulting in a negatively charged ion. This phenomenon occurs any time electrons are gained by an atom or molecule. As an electron is gained, the atom or molecule increases in negative charge. The location (commonly an electrode) where reduction occurs is conventionally named a cathode.

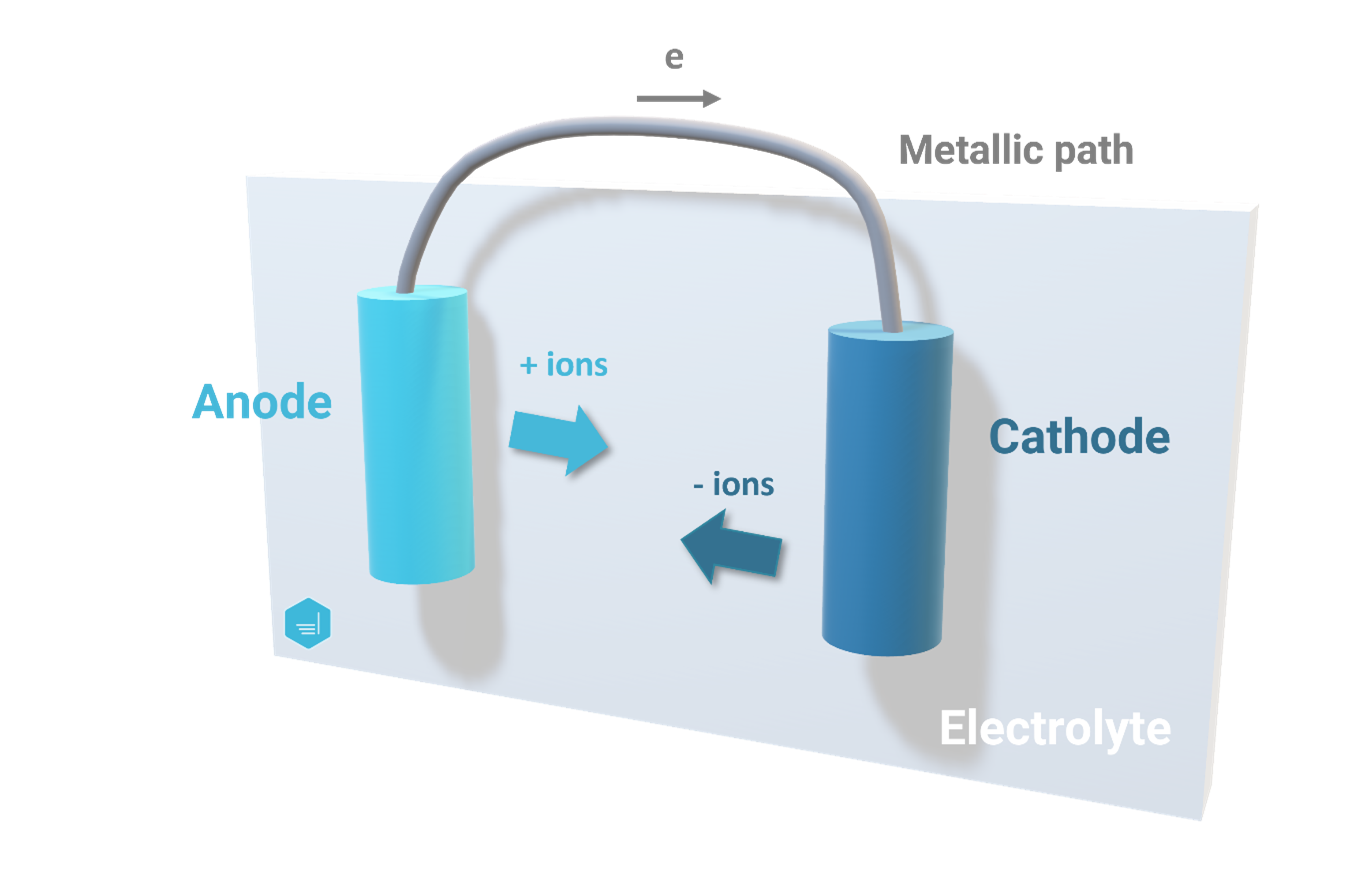

Electrochemical Cell

Electrolyte: the electrolyte is an ionized solution capable of conducting electricity. Ionization: in addition to ions that may be produced in oxidation and reduction reactions, ions may be present in the electrolyte due to the dissociation of ionized molecules. Cations are positively charged ions and anions are negatively charged ions). These ions are current-carrying charges. Therefore, electrolytes with higher ionization have greater conductivity.

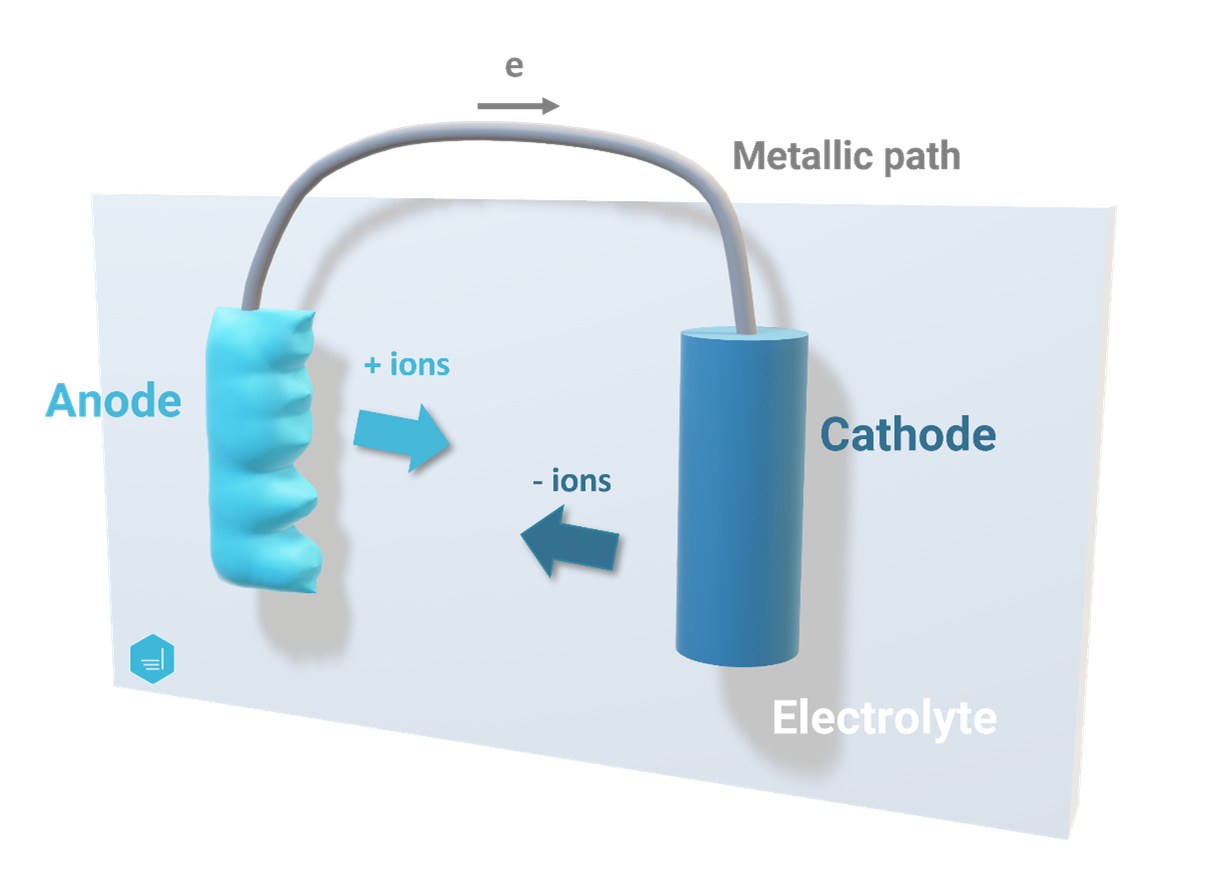

Corrosion Cell

Similarly to an electrochemical cell, a corrosion cell is made of four parts: anode, cathode, electrolyte, and metallic path.

Within a corrosion cell, corrosion occurs. Corrosion is the electrochemical process that involves the flow of electrons and ions. The corrosion (or metal loss) occurs at the anode while no corrosion is observed at the cathode (the cathode is therefore protected from corrosion).

Polarization

In the context of electrochemistry and in particular corrosion and/or cathodic protection, polarization (of a metal) refers to the potential deviation from a stabilized state due to the passage of current. When analyzing corrosion behavior, one often refers to the open-circuit potential as the “free corroding potential” and polarization refers to the shift in potential from this reference.

Within an electrochemical cell, polarization occurs both at the anode and the cathode and results in lowering the potential difference between the two. A lower potential between the anode and the cathode leads to a lower corrosion current and therefore reduced corrosion rate.

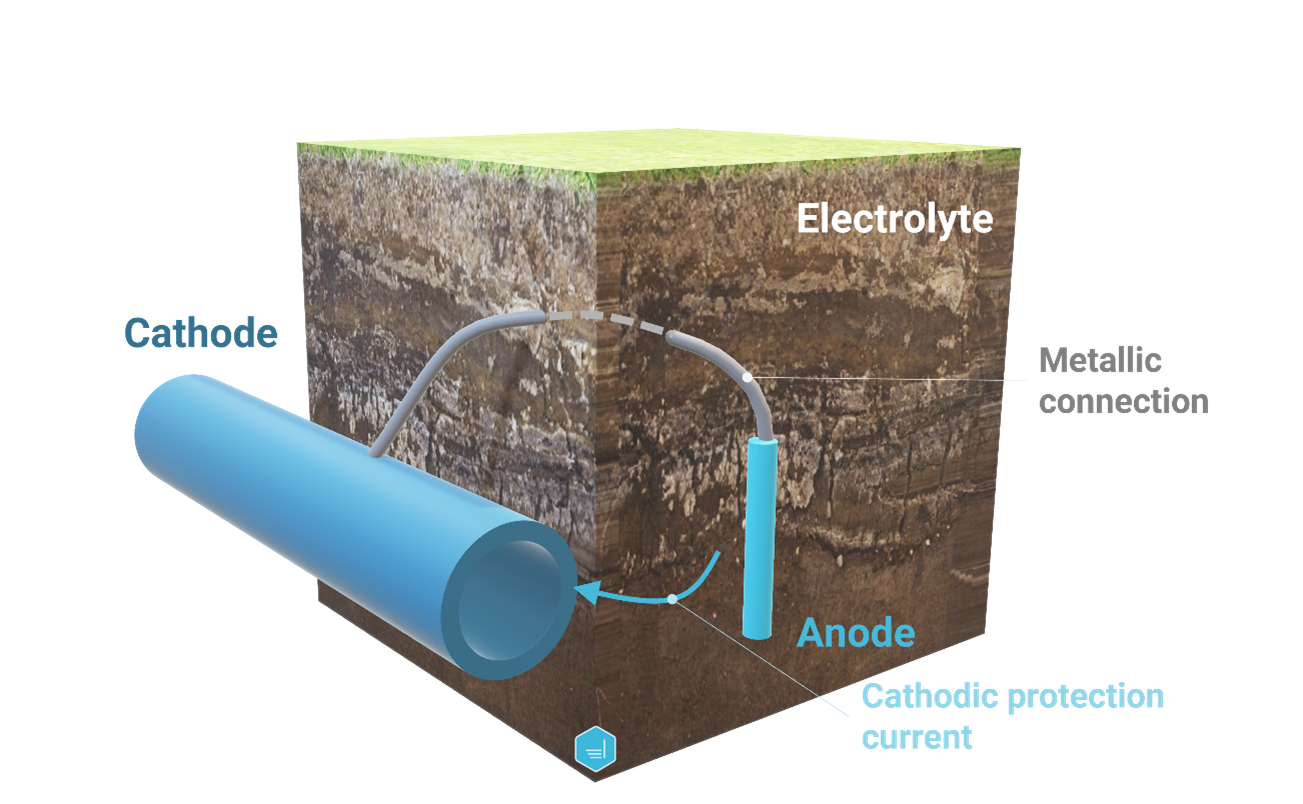

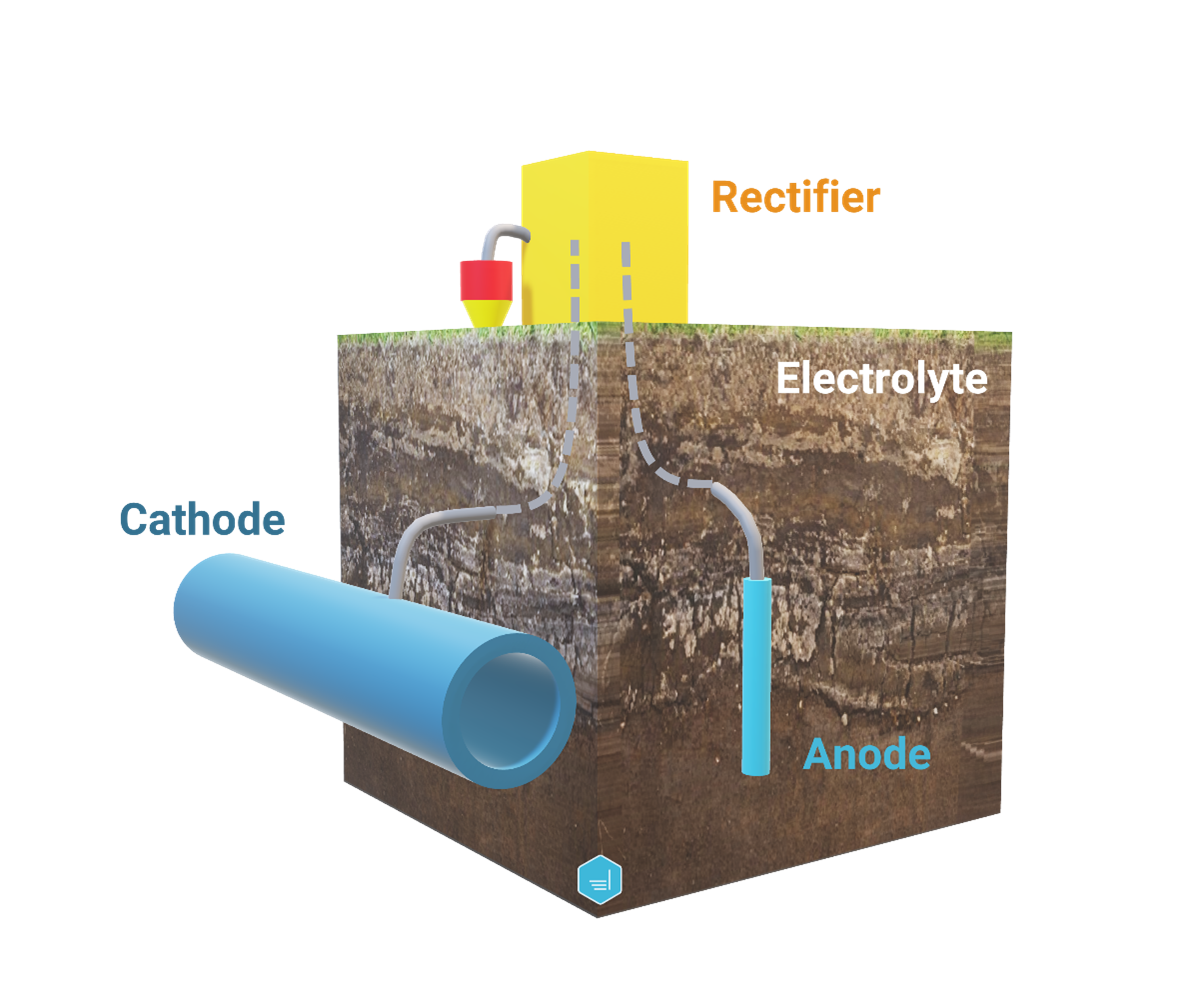

Cathodic Protection

Cathodic protection aims at reducing the potential difference to zero in-between an anodic and cathodic area. Indeed, on a corroding surface, there is a potential difference between anodic and cathodic areas that drives corrosion current. Reducing this potential difference ultimately reduces corrosion current.

In a cathodic protection installation, the corrosion is in fact not eliminated but transferred from the structure to be protected towards the anode of the system. Doing that, a cathodic protection installation transforms the structure to be protected to a cathode of a direct current circuit.

As current is involved, it is important to understand that cathodic protection can only take place when a metal is exposed to an electrolyte (water, soil, concrete, etc). It does not work within the atmosphere.

Sacrificial Anode Cathodic Protection System

A sacrificial anode cathodic protection system (also known as a galvanic protection system or SACP) is a cathodic protection installation that relies on dissimilar metal corrosion. A basic installation consists in a direct connection between the anode and the system the anode is protecting.

This type of installation has the advantage of not requiring any external current source and has minimal maintenance requirements as well as reduced cost. On the other hand, the current output is low and numerous anodes might be required to protect large and poorly coated structures. The environment in which sacrificial anodes can be installed can also be a limitation as this system is poorly effective in high-resistive electrolytes.

Impressed Current Cathodic Protection System

An impressed current cathodic protection system (ICCP) involves an external power source in addition to an anode. With this system, the power source pushes current to flow from the anode to the structure to be protected via the electrolyte. Because an external power source is used, the material of the anode could be relatively inert, in opposition to a sacrificial anode.

The use of external sources offers the flexibility to cover a wide range of voltage and current requirements and overcome the challenges related to high-resistive electrolytes. On the other hand, specific care should be taken to avoid overprotection and therefore potential coating damage or hydrogen embrittlement.

Coating

In the context of corrosion control, coating typically refers to protective coating, in other words, a layer of material added on a metallic structure to prevent the apparition and/or growth of corrosion.

Protective coating is an essential pillar of the corrosion prevention arsenal. Protecting buried or submerged structures with coating reduces the size (and therefore cost) of the cathodic protection installation as only the exposed metal surface should be protected. It is worth to mention that a regular coating inspection should be done to ensure that the coating conditions are maintained as accelerated corrosion can occur where the coating breaks (also known as holidays).

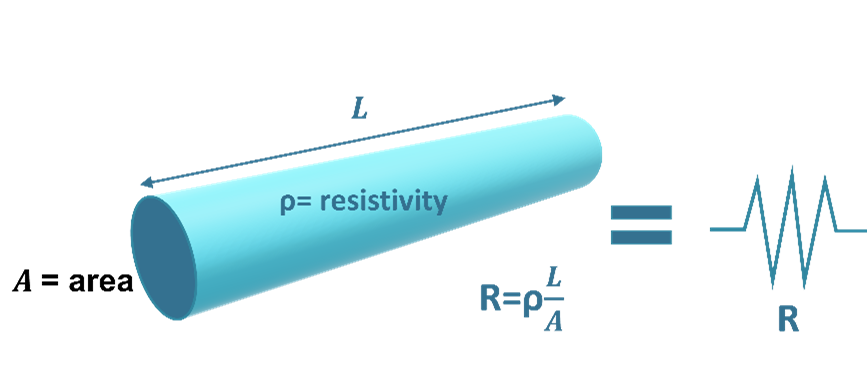

Resistivity

Resistivity is the resistance of a conductor of unit length and unit cross-sectional area. The common unit of resistivity measurement for an electrolyte is ohm-centimeter. Electrolytes dealt with in corrosion and cathodic protection include soils and liquids (water). Electrolyte resistivities vary greatly. Some electrolytes have resistivities as low as 30 Ω-cm (seawater) and as high as 500,000 Ω-cm (dry sand).

Conductivity

Reciprocal of the resistivity, the conductivity of a material characterizes the ability to support current flow. Highly conductive material should not be automatically associated with high corrosion activity. A highly conductive material only reflects the ability of this material to conduct current due to a high ion content density.

Corrosion Rate

Most of the time expressed in micron per year, the corrosion rate quantifies the amount of material that is discharged at the anode side. Corrosion rate can be computed based on Faraday’s law, expressing the weight loss as a function of the consumption rate of the metal, the current flow and the time this metal is exposed to the current.

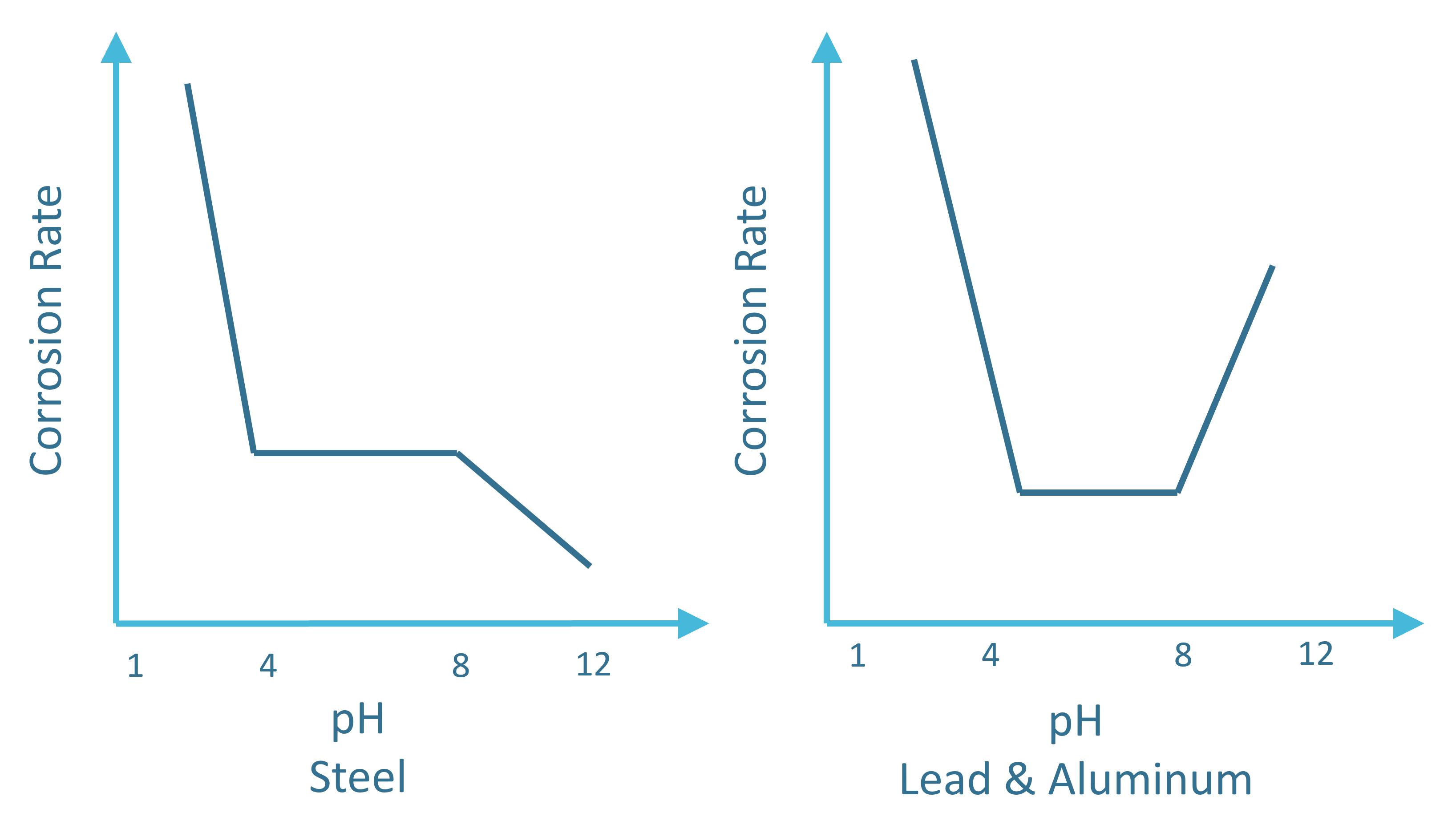

Acidity and Alkalinity (pH)

The acidity or alkalinity of an electrolyte (soil or any aqueous medium) does impact the corrosion rate. That is the reason why an understanding of the acidity surrounding the system of interest is important.

Acidity is driven by the presence of hydrogen (H+) or hydroxyl (OH-) ions. A medium is qualified as an acid medium when there is an excess of H+ ions. Acidity strength is qualified according to the pH scale. The pH is defined as the negative logarithm to the base 10 of the hydrogen ion concentration [H+].

pH = –log [H+]

For the majority of metals, the corrosion rate increases below a pH of about 4. In between a pH value of 4 and 8, the corrosion rate is fairly independent of the pH value. Above a pH of =8, the environment becomes what is called passive and corrosion rates are observed to be decreasing.

Rectifier

Commonly used in cathodic protection installations, there are three main types of rectifiers:

- Constant current: imposes a constant current over the circuit up to the maximum rated output voltage

- Constant voltage: imposes a constant voltage over the circuit up to the maximum rated output current

- Constant potential: imposes a constant potential by varying the current and voltage

DC Interference

DC Interference, also known as stray current interference, refers to an electrical disturbance issued by an electric current flowing on a structure that is not supposed to be part of the electrical circuit.

As the corrosion rate and related metal loss are proportional to the amount of current being discharged from a metal structure towards the electrolyte, DC interference is an important threat in the context of corrosion prevention and management.

Any system conducting electrical currents having two or more contact with the electrolyte could be a source of stray current. If the voltage difference in-between these two or more points is crossed by a metallic structure, a current will be created on this structure. As a consequence, corrosion will occur at the location where the current leaves the metallic structure.

AC Interference

AC interference refers to the generation of AC current and voltages induced on metallic structures. AC-induced currents or voltages are typically generated according to three mechanisms: electrostatic coupling, electromagnetic induction or resistive coupling. The related stray currents can as well cause corrosion although the metal loss is than an equivalent amount of DC current discharge.

On the other hand, the magnitude of AC stray current is often large (up to thousands of amperes during power line fault) leading to specific recommendations to mitigate alternating current and lighting effects on metallic structures.

For further reading

For more insights and information, we recommend the further reading of

- “Cathodic Protection Level 1 Training Manual”, NACE International, 2000.

- L. Bortels, C. Baeté, J-M Dewilde, Accurate Modelling and Troubleshooting of AC Interference Problems on Pipelines, NACE2012 - https://www.elsyca.com/learn/ac-interference-on-pipelines-paper-nace-2012

- NACE Standard Recommended Practice RP0177-2000, “Mitigation of Alternating Current and Lightning Effects on Metallic Structures and Corrosion Control Systems”, 2000.